Conversation

As Above, So Below

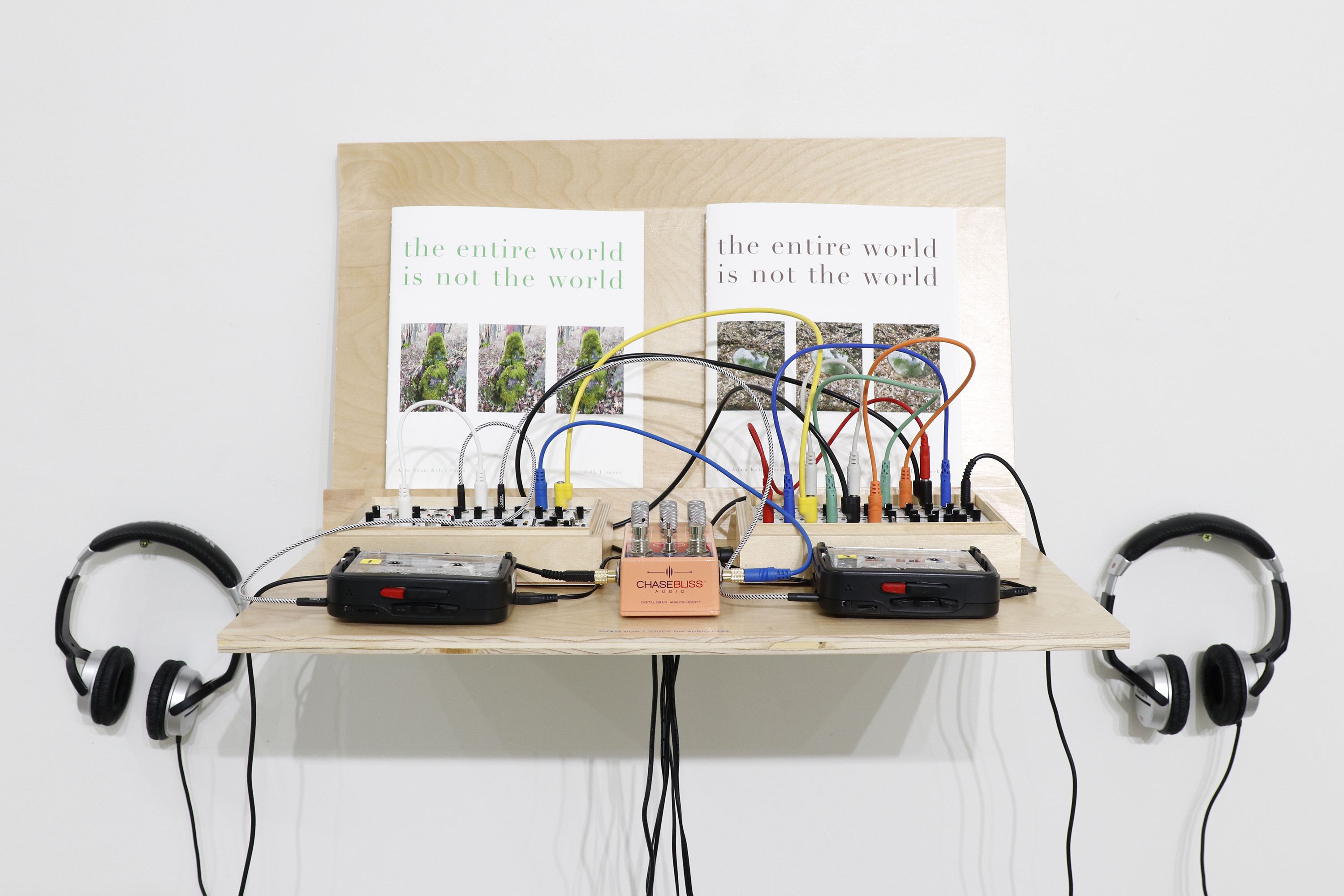

Writer Eden Redmond joined artists Maria Lux and Kyle Adam Kalev Peets in conversation about their collaborative exhibition, As Above, So Below, presented at Carnation Contemporary in June 2022. The following is edited for length and clarity.

Kyle Adam Kalev Peets I think this work is a lot quieter than anything I’ve made, or has a different sort of vibe. I think it represents a shift that’s happened in the world, or at least the way that pandemic has changed me. I think I’m more tired and I look at the world in a slower kind of way. I want to know more from it or want it to be something else.

In looking at this work, I see attempts to create portals, or an attempt to peel back what I think I understand from the world, to find something that has a new kind of meaning. Or new possibilities. Something that is the opposite of late capitalism, ownership, violence, and greed.

Eden Redmond Kyle used that word “portals,” which I know relates to one of the first works—the photos through binocular lenses. I was so curious to hear you talking about portals of entry to look for new meanings, to peel back layers and look at things from a new perspective. Because when I saw the portal prints, I immediately thought of The Blue Marble.

KAKP Wait, what’s that?

ER It’s that photograph of Earth that was taken from space 50 years ago [by the crew of Apollo 17]. It made me think about that really specific historical touchpoint, to hear you speaking now about an opportunity to see things in a new light. That photograph really reframed, for so many people, their place in the world. It inspired this whole wave of environmentalism. Now, hearing you talk about looking for new ways to reframe things and refresh things, that’s the same thing.

KAKP I think every artwork is a portal. It’s a way of seeing the world in a different way, either through someone else’s perspective or through those kinds of rhetorical shifts. “Portal” has been a word that I’ve been obsessed with for the last three years. Before that it was “threshold.” I was interested in the historical time period of the sublime and the word “sublime” being made out of two Latin words; one, limen, means “threshold” or “doorway.”

I think what I was obsessed with is the threshold moment. When you’re in that liminal space, you’re both this and that. I love the way that stretches or breaks categories, or challenges certain ontological ways of thinking about the world. So when it comes to my more recent work, I’ve been thinking about my own perception of the world and wanting to know it in a deeper way.

Like wanting to know a rock in a way that is different from a perspective that could turn it into a commodity, into a resource that could be sold. I want that rock’s essence. I think about the portal as an entry point, or even a Rosetta Stone, for knowing something differently. The Touchstone piece is exactly that. A Rosetta Stone is a kind of touchstone, a metaphorical foothold for knowing something in a different kind of way. And that Touchstone piece, you have to physically touch it to hear it.

Growing up in Canada, I grew up with this weird kids’ show called Mr. Dressup. The way that show started, Mr. Dressup is walking through a forest, and he walks through this hollow log into this other world. So that’s a fictional premise that then allows the viewer to suspend their disbelief, or at least alter belief systems to engage with the work in a different way. I wanted the portal prints (Still in Search of the Miraculous) to be near the entry of the gallery so the viewer could begin in a kind of fictional premise. The portal prints use landscape photography and binoculars. Those tools are used for seeing nature but are also used to abstract it and commodify it. They were wrapped up in, like you said, the historical context of the way that we use images to construct meaning and idealizations of nature, and also perpetuate things like settler colonialism.

I think I could just write a one word artist statement that says, “portal,” and that would work.

ER This is close to my heart ’cause I’ve written about ghost hunting reality television shows a bit. I think about the trappings of scientific aesthetics being used to try to explain really slippery things that are happening, and I think you both engage those aesthetics so thoughtfully. It’s not a simple choice to use the language of surveying tools or the aesthetics of science to discuss something that may or may not be real, and to try to pinpoint belief through the aesthetics of science, especially in a time when fact is being questioned all the time.

I was wondering if you could each speak a little bit about what is happening when you choose to focus on beliefs and perspectives through the tools and aesthetics of science, and what kind of opportunities show up, especially through play and through humor?

Maria Lux I think trying to understand how science functions outside of science has been something I’ve been interested in for a really long time. This project in particular got me thinking a lot about our desire for certainty, or the need for uncertainty, and the way that, historically, scientific discovery has functioned in giving us a sense of certainty about things.

The appeal of conspiracy theories and the unprovable just speaks so much to this desire to make sense of the world, which continues to not make sense for a lot of people for a lot of different reasons. And also how those things function with different political groups. The more I dug into it, the more I found common ground where I didn’t think there was common ground.

The Sasquatch is a great example of that because there’s really crunchy, lefty people who were like, “There’s creatures in the forest!” Then there’s super right-wing folks who are also really into Bigfoot. Those beliefs come with all these political ideologies around them. They both will borrow or steal from Indigenous ideas about human relationship to nature.

I feel like science is right at the nexus of that, of the idea of proof, the idea of evidence. What counts as evidence? When is it dangerous to critique that too much? Because then we get into this realm where fact isn’t fact, and you don’t have to believe anything. There were a lot of messy things that came up as I was thinking through this. I just held all those things in tension, which led me to think about the role of uncertainty, or being comfortable not knowing things and not needing an explanation. How could that be liberating in our ability to cope with what’s going on?

I think, Kyle, what you were saying about liminal space, applies to living in the space of not knowing things. Not being decided one way or the other seems to offer some flexibility that might be much needed.

KAKP The one thing we probably both do is borrow from science. It points to art as a unique field of knowledge distinct from science. One that can do things that science and religion and other sorts of knowledge-based systems can’t do, like contradict itself and use satire, humor, and play. Rhetorical tools like metaphor are applied to the edge, the periphery of knowledge. Religion uses metaphor to talk about things at the edge, like God or the invisible. You also can’t have science without metaphors. You wouldn’t be able to talk about, I don’t know, quarks, without a drawing of a quark, whatever that looks like. Science and the unknown are integrated into stories and metaphor, and I think that is a common linkage between our work.

ML We noticed, as we were installing the show, the recurrence of that circular shape. That’s what I think of when I think of a portal: a thing that you go through like a tunnel.

ER Absolutely. You said something, Kyle, about the portal being an opportunity to step through space and time. I wonder if we could chat a little bit about time explicitly, because you’ve each chosen pretty clear parameters for how time shapes your works.

I think about how Kyle is really opening up this opportunity to think about geologic time, the Mount St Helens stack prints specifically (Mount Analogue). And I’m thinking about Maria setting this timeline for her book that opens to the time of her birth, 1984. Then you have these popular culture references through the nineties and aughts, and you talk specifically about the kind of ideological bent toward optimism. You don’t say this explicitly, but I think your work points toward accumulation and that kind of unbound, capital growth and materialism that Kyle is asking viewers to not use as a value point for looking at natural space and objects.

You’re engaging time in such thoughtful ways, and I wonder if you could speak a little bit about how you chose those parameters. Maria, if you can chat a little bit about the specific popular cultural references that you were making.

ML For me, this project seemed like one of the more personal things I’ve ever made, even if it doesn’t seem very confessional. I felt like my reflection on the COVID times was about how different our future could be, a realization that actually sunk into me. The whole world shifted in a way that was palpable and not just theoretical. We went out and bought a deep freezer to store all the food in case of the supply chain stuff. That’s actually a real thing, which in the past was just a potential outcome.

It’s like that shock of realizing you grew up thinking one thing, and then suddenly it’s different. I’m sure lots of people come to this realization in lots of different ways. Rather than speaking on behalf of other people, this project had to be me reflecting on that.

Maybe that’s part of the connection with the broader pop culture stuff. So many people I knew loved The X-Files. For me, it was this disproportionately important thing in my thinking. When I look back, this television show should not have been this important to me, but it really set a lot of aesthetics and topics that I’ve continued to think are interesting.

I was thinking about the role of nostalgia and that desire for things not to change. Why do you always wanna go back? Back was terrible. Why don’t we want to go forward? You know, we can make changes. Things can be wonderful in the future. There’s optimism there.

KAKP That nostalgia is so misleading. It’s such a liar. I was looking at photos from a year ago and I was like, “Look at these photos, I was out and about doing things and was so proactive. That was a good, healthy part of the year.” Then I remember I was horribly depressed, and that doesn’t exist in those photographs.

ER Thinking about how you experience things differently, and realizing how much you’ve changed when you revisit familiar media. During lockdown, I tried to revisit The X-Files. I had watched it in college and loved it, and was looking for that comfort. I put on The X-Files and found that I couldn’t watch it. It was shortly after George Floyd’s murder, and I realized I can’t watch these white people running around chasing conspiracy theories when there are active efforts toERase, suppress, and murder people of color in our own country.

The imagined threat of alien conspiracy theories was no longer fun when looking at the reality of actual, coordinated governmental and social efforts to maintain white supremacy. It was such a crystallized moment of, “I can’t watch this in the same way.”

KAKP I’m glad you brought this up, Eden, because that’s a struggle that I constantly think about. How does play-based speculation or these imaginative leaps square up against what’s happening in the world right now?

I do think that trying to empathize with a rock is—on the surface—silly, childish, and naive. But below that, there are real ramifications for that gesture’s ability to horizontalize the hierarchies we make about the world. One that usually puts us on top, as humans—or white, male humans. Those hierarchies can perpetuate violence and settler colonialism ideologies. So I think the work I make in the studio is a slow burn and indirectly points to those things because of my own skillset and way of looking at the world.

I do wonder, is that play frivolous? Does it mean anything? I think another entry point for the way we think about play is perhaps through the trickster figure. The trickster is able to pull at the seams of the structures that define hierarchies and perpetuate violence.

ML I don’t know that I always do this well, but I am a firm believer that those spaces of play or humor can disarm people enough to calm down and make that space for thinking. That seems like a key component, allowing people to think differently, because we’re so regimented in our belief systems.

When somebody feels disenfranchised, they feel no one is listening to them. No one believes what they’re feeling. Nobody validates their experience. The fear is really understandable, and humor made a space for me to think empathetically about where people are coming from. Maybe something productive happens out of this space. Maybe not. But that’s the way I’ve been thinking about it.

KAKP Yeah, well, there’s the rhetorical power of humor and its ability to make difficult things more accessible. Standup comedians are so brilliant at that. Hannah Gatsby, for example, talks about suicide in their special, Nanette, and makes jokes about it. In a way, it makes it palatable. It also creates a kind of shared communal space, in the same way that sad songs or blues music can validate someone’s lived experience.

ER I would love to hear specifically about the Mega Skwrl costume.

ML In my book, there are two articles, one that suggests that Mega Skwrl is a transformed alien that’s taken the form of the squirrel to live among us. It is “mega,” because of course, and it glows, and they’re definitely real. Then there’s an article in the back that contradicts it and says maybe the whole thing’s a hoax. It was just this publicity stunt for this tiny town, to put themselves on the map. Both of those stories are templated after existing stories that many people already know, like the reframing of the Tunguska meteor crash as an alien thing.

I just lifted from that and adapted it to the idea of the Mega Skwrl. It’s left open to interpretation whether Mega Skwrl is indeed real, or whether it is a fiction or some nefarious plot.

I think it started with the idea that a flying saucer and a flying squirrel bear some verbal resemblance and visual similarities. Sometimes that has been one of the explanations for actual flying saucer sightings. Like a lot of my projects, it’s based on some real, factual information that then I build upon, or play with, or mess with. You are left not entirely sure.

ER What about your rocks, Kyle?

KAKP That came from a larger idea. I don’t know how I’m going to do this but I want to make a Cascade symphony. I want to mic up every volcano in the Cascade Range and play them at the same time.

That just got me thinking. How do you record the sound of rocks, or how could you record the movements of the earth? I drilled a hole through a rock with a quarter-inch drill bit, so I could plug in a quarter-inch jack to connect it to an amplifier. If you’ve ever played an electric guitar and are plugging in your guitar to the amplifier, and you have one end of that cord in the amp and the other end in your hand—if you touch the jack, it’ll make a sound. It will make a sound that has something to do with the way that your skin is working as an electrical conduit. If you put that jack in a rock and touch it, it does the same thing.

If you’re not touching the rock, it makes a really subtle drone. Then I just touched it while listening to it, and that just increased the current. It turned it from a kind of scratchy, white noise drone into a real bass drone. Then I started thinking, “Yeah, okay, if the earth is going to make any kind of sound, it makes sense that it’s this deep, bass drone. The drone is something that I’ve been interested in musically for a while now, because it’s this relentless thing that you have to give into. Like with drone metal for example, bands like Sunn O))) and Earth.

I started writing about some other pieces as “touchstones” metaphorically, and then was like, “Oh, hot damn, I’m an idiot. I literally just created a touchstone. That’s probably what that should be called.” I think that also alludes to touch as an alternative form of knowing, using senses other than the visual to know something like a landscape.

ER There are a couple of visual norms that you’re each playing with, to point to authority and also redirect it. Like the print tabloid, Maria. You’re invoking the formalness of a publication, right? But we can identify all of the trappings of these laughable “she gave birth to an alien” kind of tabloids. You’re using that kind of visual language to point at and undercut, and also leave the question open of how that can act as a vessel, right?

I think, Kyle, the binocular portal images are doing something similar. If you’ve looked through binoculars before, you recognize that it is a broken-down image of what you’re seeing, but you’re also challenging it and leaving this question, opening up what else it can be.

I guess I’m curious about how many of those threads and parallels you were teeing up really intentionally. How much of it was like a joyful coincidence? How much of it are you just seeing with hindsight? Can you talk about your parallels a little?

ML There were lots of weird overlaps as we talked. Kyle brought up Annie Besant’s Thought-Forms, and some illustrations from that book made it into my collages. I love the way you (Kyle) title your work, so I took some of those phrases and put them into the book. Those were some very intentional overlaps, I think.

KAKP We probably made two-thirds of the things before meeting for the first time, but Maria and I are different kinds of makers, too. Maria does, in the best possible way, a lot at the last moment. I don’t; it’s fine. I slowly chip away at it. But in that first meeting, I distinctly remember thinking, “Oh, we do the same thing but in opposite directions. I take the ordinary and say, look, that’s extraordinary. And Maria takes the extraordinary, says, actually this is ordinary.”

It was just a really lovely collaboration, because I think we have a lot in common. You know, we’re both born in ’84, both lived in Iowa, [laughter] and I think we have a similar sense of humor. The sort of speculative gestures that we make through artworks is similar. So it was a perfect balance of coincidental and then more intentional overlap.

photo credit: Brittney Connelly